This blog is a companion to FLASHBACK magazine, which I edit, and to my GALACTIC RAMBLE and ENDLESS TRIP books. All of these cover the 60s and 70s UK and US music scenes in detail. You can email me at flashbackmag@gmail.com.

Tuesday, 11 October 2022

THE CAN - Sounds, May 1970

Tuesday, 7 June 2022

IPSISSIMUS: 'A heavy sound with walloping drums'

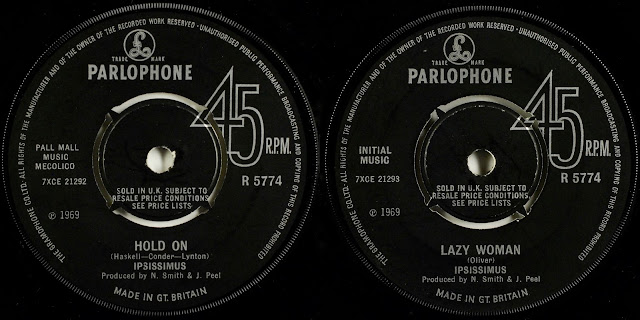

Ipsissimus released only one single, Hold On / Lazy Woman, which appeared in April 1969. The A-side is a belting cover of a song previously recorded by Rupert’s People and Sharon Tandy, while the B-side is a heavy psychedelic blues by their bassist Steve Oliver. Steve was kind enough to tell me the band’s basic history for posterity, as below...

"Len Deathridge, Reg King, Chris Evans and I met at Eastbury Secondary School in Barking in the early 60s. We formed a band called the Colts, with Len on lead guitar, Chris on rhythm guitar, me on bass, Reg on drums and a guy called Len Morgan singing. We were discovered in 1963 by Norman Newell, who produced Shirley Bassey for EMI. He didn’t sign us up but he did record Len Morgan as a solo act (under the name Tony Nelson), with us backing him.

That opened the door for us to play on sessions for various other people including Frank Ifield, and to provide backings for demos or auditions at Abbey Road on Saturday mornings. One was for Gary Glitter, although he wasn’t called that then, and another was for Graham Bonney. We were in and out of Abbey Road up until 1970, but we only saw the Beatles on one occasion, in the canteen, and we didn’t speak to them.

We used to rehearse in a youth club in Barking, which the Tremeloes also used, and produced our own demos there on a Revox machine. We got a contract with Pye as a four-piece, I can’t remember how, and made a single that came out in October 1965. The A-side was an American folk song called San Miguel and the B-side was a song of ours called Where Has Our Love Gone. The producer was Mike Smith.

In 1966 we began to focus on covers of harmony material by The Beach Boys, the Byrds and the Mamas & the Papas. We gigged two or three nights a week all over the country, often at colleges, as well as having a regular Sunday lunchtime session at the Merry Fiddlers in Dagenham. We tended to play in local pubs or halls rather than London clubs, though we did once play at the Electric Garden in Covent Garden in 1967. We supported the Herd, Episode Six, Family and various others at this time. We were aware of drugs, of course, but we weren’t at all druggy ourselves and we didn’t see an awful lot of them around.

Over the course of 1968 we developed a heavier style. Sometime that year my brother-in-law Tony Sales replaced Chris Evans on rhythm guitar and we decided to rename ourselves – the Colts seemed pretty naff by then, and our manager Dave Matthews saw the word Ipsissimus in The Devil Rides Out by Dennis Wheatley.

Dave’s brother Bob drove our van. When he heard Rupert’s People playing Hold On he suggested that we could do our own version. It was in our live set for a long time and always went down well. It became our signature song, I suppose. On stage we would stretch out on it, and Len used to do a section through an amplified Stylophone, which made various weird sounds – he even played it through a wah-wah!

We continued to provide backing for EMI auditions, some of which were performed at EMI’s head office in Manchester Square, where there was a small theatre. Various A&R men and producers and engineers would be milling around. At one Saturday morning session there we played Hold On as a warm-up and the producer Jonathan Peel and the engineer Norman Smith pricked up their ears and both offered to record us. In the end they agreed to proceed together. Dave negotiated with EMI and they paid us enough to buy new amps, for Len to buy a Fender electric 12-string (the first in the country) and for me to buy a 5-string Fender bass.

Our single was recorded over the course of a long day (and into the evening) at Abbey Road in March 1969. If you listen carefully you can hear Len playing Stylophone behind the chorus on Hold On. Norman and Jonathan were both there, but Norman did most of the work. We taped more than the two songs that were released – one other song (whose title escapes me) featured Norman playing harpsichord. When the single came out in April Tony Blackburn played it and said how awful it was, adding that it was nowhere near as good as Tamla Motown.

By then we were doing quite well as a heavy band, and often supported big-names at the Dagenham Roundhouse, the King’s Head in Romford and other venues in Chadwell Heath and Stratford. We played with bands including Led Zeppelin, Taste, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath. The problem was that they all tended to play so loudly that most of the subtlety of what they were doing was lost - at the Dagenham Roundhouse everyone had to play through the house PA system and drums were never miked.

|

| NME, April 26th 1969 |

Chris White of the Zombies then showed an interest in recording us independently, so we made some demos with him, but they didn’t get anywhere. We never split up, we just evolved into different line-ups and styles. For several years in the 70s we played pub-rock as Jerry The Ferret, then morphed into more of a country band. I had no idea anyone was interested in the Ipsissimus single until fairly recently. Sadly Len Deathridge and Tony Sales have passed away, but I’m still in touch with Reg King."

Wednesday, 9 March 2022

RICK HOPPER - CAMBRIDGE, AUTUMN 1967

In the course of researching my current book I have been looking through old copies of Varsity, the main student newspaper at Cambridge University, published every Saturday during termtime. For the eight issues of 1967's Christmas term, Rick Hopper - an undergraduate at Jesus College - contributed a pop column.

Rick had been a prefect at Eltham College, a private school in southeast London, where he was friends with Mick Jagger's brother Chris. Upon leaving they travelled around Europe together, and Rick's interests tilted towards the emerging counter-culture. He began at Cambridge in October 1966 and was closely involved with underground music there, singing with the Pineapple Truck, one of the university's two psychedelic bands, the other being 117. Sponsored to an extent by Mick Jagger, both groups spent the summer of 1967 in London, where Rick developed trenchant views on the pop scene that are reflected in his columns.

On February 23rd 1968 he compèred Under The Influence, a 'happening' in Cambridge at which Nick Drake made his formal live debut. He went on to work as an A&R man at Transatlantic Records, and perhaps his most lasting contribution to the musical world was his early championing of Kate Bush, whom he apparently introduced to his friend David Gilmour. He subsequently managed Sandpiper Books in Brighton, and is no longer among us.

I hope you'll enjoy his columns, which provide a candid and immediate insight into a lot of music that is now regarded reverentially. (As ever, click to enlarge them.) And if any of you have a copy of the two tracks the Pineapple Truck recorded in 1967 (Blow Your Mind Away and Whiskey Man), I'd love to hear them...